RFK, The Freedom Riders, And The Struggle For Racial Justice In 1961

Civil Rights was a cornerstone of John F. Kennedy’s presidential platform in 1960. He promised to introduce a comprehensive civil rights bill “within the first 100 days,” but his narrow victory, coupled with significant losses by Northern Democrats — 21 seats in the House and two in the Senate went to Republicans — had amplified the power of Southern Democrats, who now held most chairmanships in the House and the Senate.

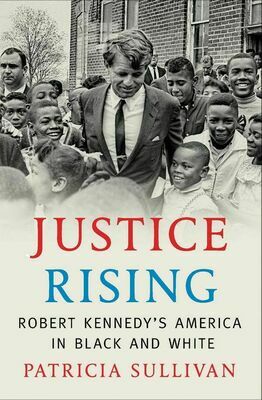

President Kennedy’s strategy was to have the Justice Department take action to enforce laws on the books but being ignored. For that, he needed someone he could trust as attorney general. “I don’t want somebody who is going to be fainthearted. I want somebody who is going to be strong, who will join with me in taking whatever risks or whatever downside exposure there was and who would deal with the problem honestly,” Kennedy told his brother Robert F. Kennedy and an aide during a December 1960 meeting.

“We’re going to have to change the climate in this country. And if my administration does the things I want to do, I’m going to have to have someone as attorney general to carry these things out on whom I can rely completely.” That someone was his brother Bobby.

President Kennedy’s choice for attorney general was widely criticized. At 35, Robert Kennedy was the youngest attorney general since Richard Rush had served under James Madison in 1814. He was not qualified by any traditional standard. The New York Times charged that he lacked experience in the practice of law — either in the courtroom or as a legal philosopher. President Kennedy dismissed the criticism of his brother. “In planning, getting the right people to work, and seeing that the job is done,” he concluded, “he is the best person in the United States.”

Bobby Kennedy knew he was a neophyte about civil rights, something he acknowledged in an interview with Look magazine early in his tenure. But he wasn’t a naif. There were people in the South who wished to perpetuate “a vast disparity” for white and Black people, he told Look, “and then use the same disparity to argue that” Black people aren’t “ready for full citizenship.” There were also Northerners “whose lives indicate they would rather talk about integration than live it” — such as newspaper editors “who preach civil rights, but belong to restricted clubs and send their children to school where there are no Negroes.” Beyond that, he acknowledged it was time for the federal government to face the racial discrimination in its own ranks — while about 13% of the roughly 1.8 million federal employees were Black people, most were in low-level jobs.

Both Kennedys moved quickly to address those governmental disparities, starting on Inauguration Day, when President Kennedy noticed the US Coast Guard contingent that marched by the viewing stand was entirely white. It turned out the Coast Guard Academy had no Black cadets; he told an aide to fix it. By the summer, the first Black professor had been hired at the academy, and in the fall four Black students joined the incoming class.

Similarly, when Bobby Kennedy toured the offices of the sprawling Department of Justice at the start of his term in January 1961, he asked an aide whether anything had struck him as strange. The aide said he was impressed to see everyone working so hard. Kennedy wanted to know why there were no Black people.

Kennedy asked the aide to report back on how many Black lawyers were working in the Department of Justice. There were 10 Black lawyers out of more than 950 working in Washington, and nine out of the 742 working in district attorneys’ offices around the country. He asked for steps to be taken immediately to open professional positions for Black people in the Justice Department. He wrote personally to the dean of every law school in the country, asking them for names “of qualified Negro attorneys of your acquaintance who might be interested in coming into the Department.”

At his first Cabinet meeting, President Kennedy discussed his impromptu order for the integration of the Coast Guard and instructed each Cabinet member to examine the situation in his own agency and take “affirmative action” in recruiting.

As for Bobby Kennedy, he wanted to build a team of lawyers at Justice who could help stop the flouting of Brown v. Board of Education, and take on voter discrimination. He did not want to pick an obvious candidate, Harris Wofford, because he was a friend and confidante of Martin Luther King Jr. Wofford recommended Burke Marshall, a corporate lawyer who had taught classes with Wofford at Howard University School of Law. Despite an awkward interview, Kennedy selected Marshall as his assistant attorney general for civil rights because he was considered “the best young lawyer in Washington.” Civil rights mattered deeply to Kennedy, Marshall said later. And the more Kennedy learned about how Black people were treated in the South, the angrier it made him. “You know, he was always talking about the hypocrisy,” Marshall said. “By the end of the year he was so mad about that kind of thing, it overrode everything else.”

Bobby Kennedy’s first move against discrimination in voter registration and school populations was to hire five additional attorneys for the Civil Rights Division and put them to work filing suits against registrars in those counties in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama where Black voters were disproportionately underrepresented on registration rolls. In the early spring, they filed 13 suits across the region.

He made his first trip to the Deep South as attorney general in early May 1961, to give a speech at the University of Georgia. Georgia voters had given the president his highest margin of victory in the election, but when the university had been desegregated in January 1961, white students had rioted in protest. The only state official in attendance at the speech would be Griffin Bell, the governor’s chief of staff, who had managed the president’s campaign in Georgia.

“If we are to be truly a great nation,” Bobby Kennedy told the crowd, “then we must make sure nobody is denied opportunity because of race, creed, or color.”

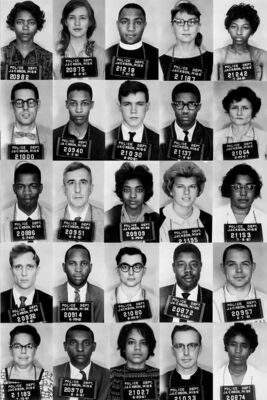

While Kennedy spoke, an interracial group of 13 men and women affiliated with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), as well as a few reporters and photographers, mostly with Black media outlets, were on the second day of their journey south to test the enforcement of Boynton v. Virginia, the 1960 Supreme Court ruling that barred segregation in bus terminals servicing interstate travel. Simeon Booker, who in 1955 as a Washington Post reporter had covered Emmett Till’s murder, was at this point Jet magazine’s Washington bureau chief covering the Freedom Rides, and had mentioned plans for the bus trip to Kennedy during an interview in April. The journalist was surprised by Kennedy’s “buoyant response — ‘I wish I could go with you!’” When Booker advised him that the riders may need federal protection at some point, Kennedy told him to call if trouble arose.

The interracial members of the Freedom Riders planned to call attention to places where the law was not being enforced, by riding together in the front of buses, which had been legal since 1946, and then to test the Boynton v. Virginia decision by integrating bus station waiting rooms, both white and Black, and other facilities along the way. To also highlight school desegregation, they planned to arrive in New Orleans on May 17, the anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education ruling.

The first significant incident happened in Rock Hill, South Carolina; young white men attacked John Lewis and a fellow rider who came to his aid, leaving Lewis, a future civil rights icon and congressman, cut up and with several bruised ribs.

But during these early stops, the Freedom Riders mostly stirred curiosity. They made a brief stopover in Atlanta, where seven riders split off to a Trailways bus, before heading farther south. Over dinner in Atlanta, Martin Luther King Jr. took Simeon Booker aside “and told me straight out,” as Booker recalled, “I’ve gotten word you won’t reach Birmingham. They’re going to waylay you.”

In Anniston, Alabama, a mob of more than a hundred men wielding clubs and bats attacked the first bus on May 14, Mother’s Day. A firebomb engulfed the bus in flames and the riders barely escaped alive. (Cars were sent to pick them up and drive them to Birmingham.) Riders on the second bus were also attacked, but it managed to continue to Birmingham, where some 50 white men were waiting, armed with bats, chains, and steel pipes. Birmingham’s commissioner of public safety, Theophilus Eugene “Bull” Connor, who two years later would assault civil rights marchers with police dogs and fire hoses, had made sure that police were not present for the bus’s arrival, promising the Ku Klux Klan 15 minutes with no interference. The mob bludgeoned the riders as they entered the bus station and also attacked the journalists. Several riders had to be hospitalized. (Years later, it was revealed that FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover knew of the attack in advance but failed to notify the attorney general.)

To Be Continued Next Week

Please support The Community Times by subscribing today!

You may also like:

Loading...

Loading...