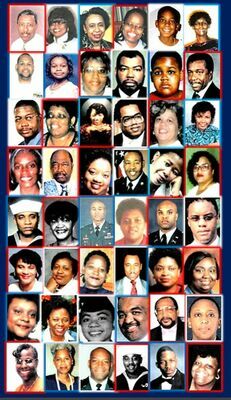

Twenty years after the September 11 attacks, the faces and stories of hundreds of Black victims are rarely seen and told

FIRST ROW: Yeneneh Betru, 35, Carrie R. Blagburn, 48, Angelene C. Carter, 51, Sharon A. Carver, 38, Bernard C. Brown II, 11 and Sara M. Clark, 65. SECOND ROW: Julian Theodore Cooper 39, Asia Cottom, 11, Ada M. Davis, 57, James D. Debeuneure, 58, Rodney Dickens,11, and Eddie A. Dillard, 54, THIRD ROW: Johnnie Doctor, 32 Jr., U.S. Navy, Technician Amelia V. Fields, 46, Sandra N. Foster, 41, Cortez Ghee, 54, Brenda C. Gibson, 59, and Diane Hale-McKinzy, 39. FOURTH ROW: Carolyn B. Halmon, 49, SSG. Jimmie I. Holley,54, Peggie M. Hurt, 36, SGM. Lacey B. Ivory, 43, Brenda Kegler, 49, and Samantha L. Lightbourn-Allen, 37. FIFTH ROW: OS2 Nehamon Lyons IV, 30, Ada L. Mason-Acker, 50, MAJ. Ronald D. Milam, USA, Jr., 33, Odessa V. Morris, 54, MAJ. Clifford L. Patterson, Jr.,33, and Scott Powell, 35. SIX ROW: Marsha D. Ratchford, 34, Cecelia E. (Lawson) Richard, 41, Judy Rowlett, 44, SGM. Robert E. Russell, 51, Janice M. Scott, 46, and Antionette M. Sherman, 35. SEVENTH ROW: Edna L. Stephens, 42, Hilda E. Taylor, SGT. Tamara C. Thurman, 25, LCDR. Otis V. Tolbert, 39, SSG. Willie Q. Troy, 51, LTC. and Karen J. Wagner, 40. EIGHTH ROW: SSG. Maudlyn A. White, Sandra L. White, 44, MAJ. Dwayne Williams, 40, Kevin W. Yokum, 27 Edmond G. Young, Jr.,22, Lisa L. Young, 37, and Donald M. Young, 41.

FIRST ROW: Yeneneh Betru, 35, Carrie R. Blagburn, 48, Angelene C. Carter, 51, Sharon A. Carver, 38, Bernard C. Brown II, 11 and Sara M. Clark, 65. SECOND ROW: Julian Theodore Cooper 39, Asia Cottom, 11, Ada M. Davis, 57, James D. Debeuneure, 58, Rodney Dickens,11, and Eddie A. Dillard, 54, THIRD ROW: Johnnie Doctor, 32 Jr., U.S. Navy, Technician Amelia V. Fields, 46, Sandra N. Foster, 41, Cortez Ghee, 54, Brenda C. Gibson, 59, and Diane Hale-McKinzy, 39. FOURTH ROW: Carolyn B. Halmon, 49, SSG. Jimmie I. Holley,54, Peggie M. Hurt, 36, SGM. Lacey B. Ivory, 43, Brenda Kegler, 49, and Samantha L. Lightbourn-Allen, 37. FIFTH ROW: OS2 Nehamon Lyons IV, 30, Ada L. Mason-Acker, 50, MAJ. Ronald D. Milam, USA, Jr., 33, Odessa V. Morris, 54, MAJ. Clifford L. Patterson, Jr.,33, and Scott Powell, 35. SIX ROW: Marsha D. Ratchford, 34, Cecelia E. (Lawson) Richard, 41, Judy Rowlett, 44, SGM. Robert E. Russell, 51, Janice M. Scott, 46, and Antionette M. Sherman, 35. SEVENTH ROW: Edna L. Stephens, 42, Hilda E. Taylor, SGT. Tamara C. Thurman, 25, LCDR. Otis V. Tolbert, 39, SSG. Willie Q. Troy, 51, LTC. and Karen J. Wagner, 40. EIGHTH ROW: SSG. Maudlyn A. White, Sandra L. White, 44, MAJ. Dwayne Williams, 40, Kevin W. Yokum, 27 Edmond G. Young, Jr.,22, Lisa L. Young, 37, and Donald M. Young, 41.

They were accountants, college-educated professionals, high-ranking military officers with Purple Heart medals, husbands, wives, mothers, fathers and even children. Proud citizens living the American Dream, they were also Black when they died 20 years ago on September 11, 2001.

For years they led productive lives and managed successful careers before they perished when a hijacked American Airlines Boeing 757 smashed into the headquarters building of the U.S. Department of Defense, the Pentagon, that day.

Today, 49 of the 125 victims of the terrorist attacks at the Pentagon remain a group of forgotten Americans whose names and faces are rarely shown or mentioned on the anniversary of the most horrific day in American history.

This weekend, the nation will reach another milestone as it marks the 20th Anniversary of the September 11 attacks.

There will be speeches, moments of silence and the reading of the names at the 911 Memorial site in New York where the World Trade Center once stood before terrorists flew two planes into them, killing 2,996 people.

At the Pentagon, 189 people died after one part of the massive building was struck by an airplane. In Shanksville, Pennsylvania, 44 people died when terrorists crashed United Airlines Flight 93 in a vacant field.

Many Americans may not know that hundreds of Blacks were among those who perished that day. About 267 Blacks died that late summer morning in New York City, Washington, D.C., and Shanksville, PA. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 215 Blacks died in the attacks on the World Trade Center. About 49 Blacks died at the Pentagon and three died in Shanksville, PA.

September 11 has grown into a hallowed, solemn day that is laced with American patriotism and reverence of the nation’s military. But year after year, on the anniversary of the worst terrorist attack on American soil, news organizations run stories on the lives of the victims, many of whom were white, Jewish, accomplished and affluent citizens who had high-paying jobs on Wall Street and in Washington, D.C., before their lives ended.

The images of white businessmen escaping the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center injured, in suits caked with debris, has somehow given many the impression that the September 11 attacks were tragedies affecting America’s upper crust and privileged elite. In reality, the attacks were a tragedy that affected all races, including Blacks.

In death, as in life, the Black victims were also well-educated Black professionals and military officers. To some, it is another event that makes Blacks feel less American and less patriotic about a country they spent their entire lives helping to build.

In 2011, on the Tenth Anniversary of the attacks, Time Magazine published “Beyond 9/11: Portraits of Resilience,” a photo-rich commemorative edition. Of 64 pages, there were no photos of identifiable Black Americans. Asked about the omission by the online Black publication The Root, a Time Magazine spokesman declined to comment. In 2006, Jason Thomas, a former U.S. Marine who helped to rescue a pair of Port Authority police officers in the rubble, was portrayed by a white actor in the film “World Trade Center.” But that same year, Gary Commock, a Black actor, played the late First Officer Leroy Homer in “United 93,” which chronicles the September 11 crash in Shanksville, PA.

In 2002, the New York Times reported that of the 343 firefighters killed that day, about a dozen were Black and a dozen were Hispanic. The story came amid a controversy over a decision to create a memorial statue that was based on three white men.

After the Twin Towers at the World Trade Center collapsed on September 11, Paula Edgar from Brooklyn lost her mother, Joan Donna Griffith, according to an article in Essence Magazine on the 15th Anniversary in 2016. She was in the South Tower, which was the first to collapse after both were hit.

“The day it happened it was very jarring because I was 3,000 miles away from home; I was living in California,” said Edgar, who had moved to California in 1997. “Being so far away and knowing that everything was happening, and my family was being impacted was really hard to deal with. I felt like I couldn’t reach out and touch them.”

“Phone lines were down and the only real connection that you had was through the television,” Edgar told Essence. “I had gotten this sixty-inch television two days before so, literally, I saw the towers fall really crisp and really clearly first thing in the morning on that Tuesday.”

Edgar said her “mother didn’t have the opportunity to live her life and fulfill the dreams that she had.”

All three September 11 memorial sites have since erected living memorials dedicated to all the victims. Their names are etched in granite and marble slabs that attract visitors year-round. None have the pictures of the victims, which could help educate future generations about the full story of the victims of September 11.

One online publication where visitors can learn the identity of the September 11 victims and their individual stories is The Pentagon Memorial Fund website. The platform has pictures and stories of every victim who died during the attack on the Pentagon.

The Crusader visibly identified 49 Black victims. At least 14 worked in the Pentagon, 17 served in the U.S. Army and eight served in the U.S. Navy. At least eight were budget analysts at the Pentagon and four were accountants there. Three were teachers in the Washington, D.C., area and three were elementary school children who were just 11 years old when the building was hit.

The website also lists all the victims in the World Trade Center attacks, but it understandably doesn’t include all the photos of the thousands of victims. But one can get a full scope of the lives of Blacks who were at the Pentagon or on American Airlines Flight 77 during the attack.

The flight was scheduled to travel from Dulles International Airport near Washington, D.C., to Los Angeles International Airport on September 11, 2001.

Five hijackers boarded the flight. One of the hijackers, Hani Hanjour, was a trained pilot. About half an hour after takeoff, the hijackers took control of the aircraft. At 8:54 the westbound plane turned to the south, a deviation from its flight plan. Two minutes later, the airplane’s transponder was turned off. Radar contact was also lost.

The hijacked plane traveled undetected back toward Washington for 36 minutes. At 9:32 a.m., air traffic controllers at Dulles found an unidentified aircraft traveling east at a high rate of speed and notified officials at Reagan National Airport. At 9:37 a.m. Flight 77 slammed into the Pentagon.

The plane hit the outer wall between the first and second floors of the building. The jet fuel exploded into a fireball. A half an hour later, a section of the building above where the plane hit collapsed. By that time, most people working at the Pentagon had been evacuated. However, 125 people working in the building were killed, as were the 64 crew, passengers, and hijackers on the plane.

The Black victims of the 911 terrorist attacks are for the most part remembered as nameless and faceless statistics. But they, too, have stories, of family, career, school, of lives ripe with future plans.

One Black victim, Amelia V. Fields, was celebrating her 46th birthday that day. Her husband and high school sweetheart, William Fields, a retired Marine Corps master sergeant, slipped out of their home during breakfast to place a surprise birthday card in her car. While she headed to work at the Pentagon, where she was a civilian secretary for the Army, he baked a chocolate cake for when she would have arrived home that night.

Fields has not been heard from since the attack. Her husband remains uncertain how to register certain aspects of her fate. She had worked there for only two days, having been assigned previously to Fort Belvoir in Fairfax County, Virginia.

Another victim, Sara M. Clark, 65, and her fiancé had decided to have their wedding reception at a yacht club in Baltimore. The Sunday before Tuesday, September 11, they went shopping for wedding bands. On Tuesday morning, they kissed, embraced and said, “I love you,” to each other before she left their Columbia home for Dulles International Airport.

Dr. Yeneneh Betru, born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, immigrated to the United States in 1982 with the dream of becoming a physician. He attended high school at the Abbey School in Colorado, College at Loyola Marymount in Los Angeles, Medical School at the University of Michigan, and later completed his residency at Los Angeles County–USC Medical Center. During the last three years, he worked as the Director of Medical Affairs for IPC–The Hospitalist Company in Burbank, California. He was only 35 years old.

Major Clifford Patterson is one of four high-ranking Black military officers who earned the prestigious Purple Heart medal before he perished in the Pentagon attack. Patterson, who served in the U.S. Army, left behind a wife and two young sons. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Eddie Dillard, 53, from Gary, Indiana, was on his way to California, where he planned to paint a house he owned in Los Angeles and visit his only child, who lives in the East Bay area. He was a retired marketing executive with Philip Morris Tobacco Company.

Asia Cottom, 11, had just started sixth grade at a new school, eager to learn and pleased to be at the campus where her father worked. She and her teacher Sara Clark were selected to take a four-day trip to California to participate in a National Geographic Society ecology conference. They never made it.

Another 11-year-old victim, Rodney Dickens, grew up in several tough Washington neighborhoods, but he had always made the honor roll. His life was cut short when he and his teacher at Ketcham Elementary School boarded American Airlines Flight 77.

Please support The Community Times by subscribing today!

You may also like:

Loading...

Loading...